← Blog from Guindo Design, Strategic Digital Product Design

The interface effect

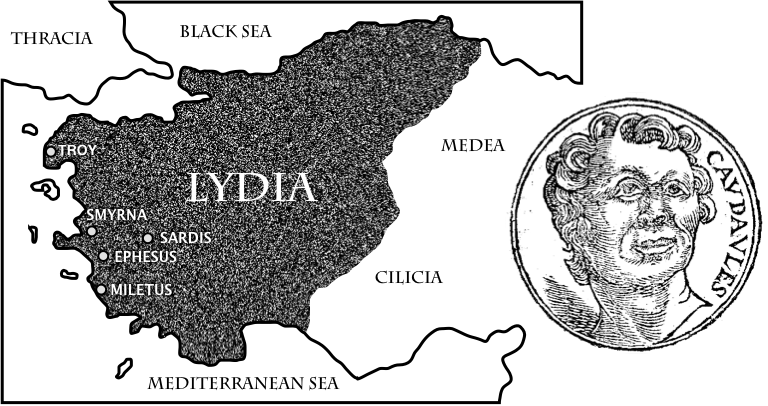

No one knows for sure how Giges came to the throne of Lydia (680 BC), which has given rise to countless tales and legends. At that time, Lydia was ruled by Candaules, a man who according to Herodotus was very much in love with his wife Nyssia.

Plato, in Book II of The Republic, mentions that while Giges was a shepherd, after a storm he found a half-buried horse, and inside it a magic gold ring that, when turned on his finger, made him invisible.

The Ring of Giges

This myth has had great influence in philosophy and literature to exemplify that all people are unjust by nature, and that this behaviour only comes to the surface when we are “invisible”.

The Herodotus' earlier version of the story has a more erotic-festive overtone...

It seems that Candaules was obsessed with his partner's beauty and was constantly boasting about her beauty. Giges, one of his servants, did not give him much credit, and to convince him, the king invited him to see her naked on the sly.

Obviously this gesture did not please Nyssia, and in revenge against Candaules, she gave Giges the choice between being executed or killing the king and taking the throne. A difficult decision for Giges.

By passively observing, Giges projects himself into the figure of Candaules, generating a fictitious personality without autonomy, as if he were watching a film. candaulism is a type of voyeurism where the subject obtains erotic gratification by exposing his partner to other people.

Cinema forces us to put on the Ring of Giges, when the lights go out we become voyeurs of the world, sometimes exposing ourselves to situations that we would not accept in the real world (terror, violence, exploitation, sex...).

“To be cinematically present in the world, to experience the pleasure of films, you have to be a bit of a masochist”.”

Stanley Cavell

We voluntarily submit ourselves to certain pain and humiliation, annulling our own capacity to act on the situation. But this submission is at the same time an exercise in empathy, we identify with the characters and the story, and sometimes we feel recognised.

However, we do not cry at the computer as we cry at the cinema.

If the cinema screen is always projected towards us, the computer screen always faces away from us, like a window. In the cinema you tilt your head backwards. At the computer you lean forward.

The cinema is an altar. The computer is a rosary.

The computer is an anti-ring of Giges where the scenario is inverted. The wearer is free to wander in plain sight, while the world, invisible, is represented as other. The world no longer indicates to us what it is, we indicate to it, and in doing so, the world materialises in our idealised image.

The interface effect

This metaphor, of which I have taken the license to give it a twist, is briefly discussed by Alexander Galloway in “The Interface Effect”, a book published in early 2013, where the author makes an exhaustive reflection on the implications that interfaces have in the definition of our world.

It is a book that straddles anthropology and philosophy, where Galloway moves from old conceptions of media and interfaces as objects, to the effects of interfaces that mediate between people and the world around us (from relationships to global events, etc.).

Media such as radio, film and television have historically changed our sense of space, time and social relations, conditioning our experiences and perceptions. They have gone from defining the message (Marshall McLuhan, 1960s) to determining our situation (Friedrich Kittler, 1980s).

With the advent of the World Wide Web in the 1990s and the proliferation of mobile devices, we have experienced dizzying transformations in the frequency, speed, scale and quality of human communication. The Covid-19 pandemic has further catapulted our dependence on technology to communicate, making us experience first-hand a dystopian cocktail of science-fiction narratives.

For Galloway, the interface effect is one where the computer goes from being an object (or a creator of objects), to an active process or threshold that mediates between two states. An interface is not a stable object projected on a screen, it is a multiplicity of processes. It is «not a thing»; it is «always an effect», a technique of mediation or interaction.

Computers define horizons of possibility.

Layers and device reduction

We are used to thinking of an interface as a user-friendly surface that hides the depths of the code; for Galloway, however, it serves as a way of thinking in terms of interrelated «levels» or «layers», and he presents some historical examples:

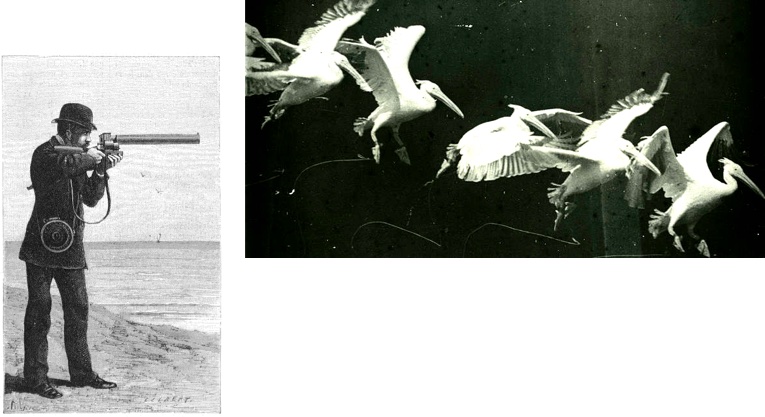

Étienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904), was a French physiologist considered to be one of the pioneers of photography and film, inventor of several scientific measurement tools and data representation techniques. At one point in his life he became fascinated by the movements of birds, and adopted a different approach to capturing a sequence of movements in several images. Chronophotography at the time required positioning and synchronising up to 12 different cameras, the task was therefore to get rid of 11 cameras to perform the same task.

Marey devised the chronophotographic shotgun in 1882. Perhaps inspired by the design of the Colt revolver, which had reduced the need for six pistols to one, it was an instrument capable of taking 12 consecutive frames per second, recorded in the same image. A snapshot of 12 different moments.

Television did something similar with cinema, perhaps inspired by radio, by uniting several image narratives in a single channel, and then later allowing several narratives to coexist simultaneously, through several channels. Now the transmission channels are almost infinite.

Computers represent the final link in the reduction of devices, they have not only made countless analogue tools obsolete, they have also reduced all dimensions to zero. Nothing takes up space and everything happens at once. The ultimate pistol.

Software and ideology

Galloway elegantly weaves connections between the interfaces he analyses and the ideological apparatuses that function within them.

An ideology is not something that can be solved like a puzzle or cured like a disease. Ideology is best understood as a problematic, i.e. theoretical problems arise, are generated and sustained precisely as problems in themselves. And there is nothing more attractive to software than solving its own problems through software.

“Software is a functional analogue to ideology”.”

Wendy Hui Lying Chun

In software, code obfuscation or «information hiding» is used to make code more modular and abstract and therefore easier to maintain. The code is never seen as it is. Instead, code must be compiled, interpreted and parsed and hidden by even larger code balloons.

But despite its obfuscation, code has arguably become as important as natural language, as it allows commands to be executed that the machine can interpret, and things happen.

Code running on a machine is performative in a much stronger sense than natural language. When a judge says »I declare this session open» or «I declare you joined in marriage», these sentences can result in changes in people's behaviour, but the performative force of language is conditioned by complex chains of mediation and interpretation. Conversely, code executes changes in machine behaviour, and through the network can initiate other changes that affect our reality. Ordering food from the palm of our hand, or paying with a flick of the wrist, is something like an incantation.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Arthur C. Clarke

In short, this is a highly recommendable book if you feel like reading it to take a bit of distance and a critical perspective on the technology that surrounds us.