← Blog from Guindo Design, Strategic Digital Product Design

Rudolf Arnheim and Visual Thinking

Surely many of you, even today, have come across UX deliverables riddled with text, instructions and descriptive phrases, which attempt to solve through the use of written language what could not be solved visually. This kind of solutions, generally, make the interface very difficult and not very fluid, as they do nothing more than patching design problems.

This inertia, increasingly in disuse, is perhaps due to the fact that for a long time in this country, design or visuals were discredited among Usability and Information Architecture professionals. Design was completely separated from usability attributes, it was very common to hear phrases like “that's a design problem” or “let the designer solve it”. This was largely conditioned by the multidisciplinary background of the pioneers of the profession.

But why this rejection and difficulty in interpreting and valuing the visual?

In Western cultures, language (and therefore thought) is based on a semantic structure, we perceive the world by a series of descriptive knowledge which inevitably leads us to a scientific and linear logic, we look for an unambiguous meaning of things: what, how, when and why.

Visual language and thinking does not work like that, visual elements do not have an unambiguous meaning, which already clashes with the way most people think.

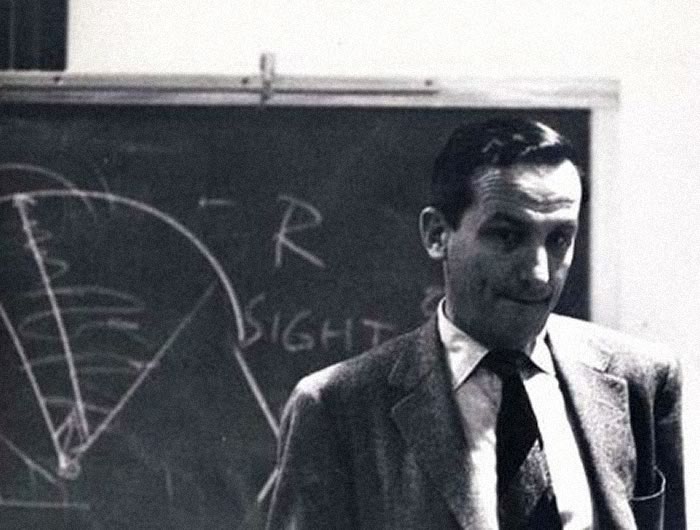

One of the pioneers in analysing and dignifying visual thinking was Rudolf Arnheim, a psychologist and philosopher born in Berlin in 1904, who was greatly influenced by Gestalt psychology and Hermeneutics. For Arnheim, modern man is permanently beset by the world of language and uses it too much to relate to the world.

Rudolf Arnheim teaching a class at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville. SLC course catalogue, 1950s. Author unknown.

In his book Visual Thinking (1969), a classic in schools of Art and Design, he states that there are other ways of apprehending the world based on the senses, for example, on sight. Language serves us to name what has already been heard, seen or thought, but abusing it can paralyse us in the resolution of problems through intuitive creation.

«All perceiving is also thinking, all reasoning is also intuition, all observation is also invention».»

Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye (1954)

How do we think visually?

For Arnheim, intelligence is impossible without perception. The ideas or concepts we have of an object condition how we perceive it. Perception and thought act reciprocally. For example, a visual stimulus about an unfamiliar object attracts our attention more than another with which we are familiar (e.g. an exotic fruit). This continuous feedback between stimulus and intellect facilitates our daily life.

By creating visual artefacts (with greater or lesser definition or conceptualisation), we do nothing more than project our ideas, putting them in order on paper in order to re-perceive and elaborate them better. The visual representation of concepts helps us to think and connect ideas with the real world, for Arnheim it is vital to be down to earth. We cannot teach mathematics without giving practical examples.

“We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us”.”

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (1964)

How do we analyse what we perceive visually?

According to Arnheim there are three attitudes of observation:

- The most common way is to isolate the object in order to perceive it in a pure state, i.e. to synthesise its idea/concept in its simplest form. This is the way we are taught to draw from an early age, for example by scribbling the typical house. When we draw from memory, from our “internal designs” we evoke eidetic images, images imprinted in the memory or the concepts of the stimuli we have received. The higher the level of abstraction, the greater the image's capacity for universal representation.

- Another attitude is not to isolate the object from its context, but to merge it with it so that the attributes of the two blend together. This would be the pictorial gaze, in which, when an image is analysed, light, shadows and colours are perceived in an attempt to construct a representation similar to the one we perceive with sight.

- The third option is to analyse the object creatively, from multiple points of view and possibilities. Changing its meaning, looking for new uses and possibilities of interpretation.

These 3 forms of observation and visual thinking are in continuous and combined use in our profession. For example, the first would be used to represent diagrams and abstract concepts. The pictorial gaze would be that of the visual designer, who needs a realistic approach to the final product. And the third is the one we use to devise and look for new possibilities, both in the visual interpretation of the interface elements and in the interaction.