← Blog from Guindo Design, Strategic Digital Product Design

Charles Sanders Pierce: Pragmatism, Abduction and Semiotics in Design

Of all the schools of thought, pragmatism is the only philosophical tradition that was born in the United States, explicitly reflecting the ideals of America's founding, and more particularly, the political, institutional and scientific context of the early 19th century. Its ideas had a profound impact on how American society was shaped, changing the way its citizens thought and defining its institutions.

From a perspective of how we understand design today, and more specifically from Europe, I think it is worth knowing this influence and being aware of its origin. Ideas take a long time to take hold in a society, sometimes it is necessary to go back centuries to understand how we act. I have always had the feeling that we live the practice of design in great dissonance with our counterparts in other latitudes, in constant conflict with the basic education we have received, and exercising it in a context that always mentally navigates in another direction.

Pragmatism is a school of thought that speaks directly to people interested in social change. At the end of the 19th century there was much optimism and confidence in intellectuals as the engine of progress. This does not detract from the fact that we are able to read critically and with perspective the whole influence of the pragmatist movement, which was conceived by privileged intellectuals of the economic elites, in a completely different historical context.

The Metaphysics Club

Around 1870, a group of young students met in a Harvard club to discuss their ideas. From the “Metaphysical Club”, an ironic name, since their ideas were completely contrary, emerged the main exponents of pragmatic thinking, a current of philosophy that defends that theories must be linked to experience.

Among the most active members of the group were Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, the former as the creator of the pragmatic method and the latter as its main disseminator. We also find names such as George Herbert Mead and John Dewey, who stood out as the most influential philosopher who put the principles of pragmatism into practice in education.

They were all strongly influenced by the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin's «On the Origin of Species» and the evolutionary perspective on life, ideas which, for pragmatic thinking, put the emphasis on interactions and adaptation between organism and environment.

Pragmatism emphasises the integration and implementation of knowledge, rejecting Cartesian radical doubt and the dualistic worldviews of the time: mind and matter, reason and emotion, theory and practice, and so on. They focus on experience (or experience, if we translate it better into English) as the locus of all meaning. Continuity, flow and change become the main axes of their discourse, which triggers an epistemological theory that emphasises process and experimentation.

As I think the ideas are best understood with a bit of context about the lives of the authors, let's give a short introduction to each of the members of the group and their contributions. Needless to say, they will all be very familiar to you.

Peirce, clarifying ideas

Why is your eye like a thief dodging whips? Because it's under the eyelashes.

C. S. Pierce

Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), was a precocious and privileged child with a great deal of intellectual stimulation. His father was an eminent mathematician at Harvard and his interest in logic began at an early age. After graduating, he worked for the US government doing geodetic research. For more than thirty years, Peirce was involved in practical and theoretical problems associated with making scientific measurements. This experience was undoubtedly vital to his views on philosophy and logic.

Although he wrote extensively on many philosophical topics, he never compiled his thoughts into a book. His writing style, like his character, was not easy, lacking the clarity that might have made his views more accessible. He was a complicated character and not in very good health, which meant that he did not form many friendships and throughout his career he did not receive much support or recognition.

In his seminal article “How to make our ideas clear”, Peirce seeks a reason to think, a sense of reality to move away from the earlier philosophical tradition. A logical maxim, rule or method clear about the purpose of concepts and hypotheses:

We clarify a hypothesis by identifying its practical consequences. If a philosophical question has no practical consequences, it is of no interest.

For him, philosophy and logic were sciences in themselves, indeed, he understood philosophy to be the philosophy of science, and logic to be the logic of science. Pragmatism is a method that formulates how to clarify our ideas. To determine the meaning of an idea, we will follow the scientific method: one must “test” that idea in the «objective world” and the results of this experiment will constitute the meaning of the idea. If there are no results, or if the results do not make sense, the idea is most likely not meaningful.

Surprise abductees

Before Peirce, logic divided arguments into two subclasses: deductive arguments (necessary inferences) and inductive arguments (probable inferences). Peirce introduced a third: abductive inferences, which he also referred to as hypotheses or introductory inferences.

The scientific method would begin with abduction, an explanatory hypothesis based on a “surprising” or striking observation. Subsequently, through deduction, conclusions would be drawn as to what phenomena should be expected, if the hypothesis is correct. The method closes with induction, when experiments are carried out to determine whether or not the deduced results are obtained.

Unlike deduction or induction, abductive logic allows for the creation of new knowledge and ideas: B is presented as a best guess as to why A is occurring, but B is not part of the original set of premises. And unlike deduction, but equally true to induction, the conclusions of an abductive argument can turn out to be false, even if the premises are true (Kolko 2010).

“The abductive suggestion comes to us like a flash. It is an act of understanding, though an extremely fragile understanding. It is true that the different elements of the hypothesis were in our minds before; but it is the idea of putting together what we had never before dreamed of putting together, which shows the new suggestion before our contemplation”.”

Design synthesis is fundamentally a way of applying abductive logic. The activity of defining and creating connections actively produces new insights and knowledge. The process of creating meaning by manipulating, organising and filtering data relies on specific skills and techniques of the designer. For example, reframing a situation from a particular user perspective, graphically mapping concepts or experimenting with design patterns.

Icons, indexes and symbols

Strongly connected to the ways of arguing the scientific method would be the theory of signs or semiotics, that is, how we interpret or represent signs.

A sign is something that represents someone or something in some aspect or capacity. It creates an equivalent representation in someone's mind, not in all aspects, but in reference to some kind of «idea» or basis. The relationship between an object, a sign and an interpreter is genuine, no one interprets a sign in the same way.

The signs in turn are divided into three types:

- icons are signs that show their objects through similarities or resemblances. An ✏ is an icon of the object it represents. However, its meaning lies in its connotation.

- The indices are signs that indicate their objects causally. Smoke is an index of fire and a symptom is an index of a disease. The meaning of indices lies in their denotation, since the main quality of an index is to draw attention to its object by making the interpreter pay attention to the object.

- symbols are words, hypotheses or arguments that depend on a conventional or customary rule. They have a pragmatic meaning, i.e. they are intended to be used by people knowing how they will be interpreted.

According to Peirce's theory of signs, the meaning of a symbol, such as a word, is based on social conventions and therefore its pragmatic meaning is dynamic, as it continues to evolve over time. When a sign triggers a subsequent sign (an interpretation) in someone's mind, an infinite chain of interpretation, development or ideas begins.

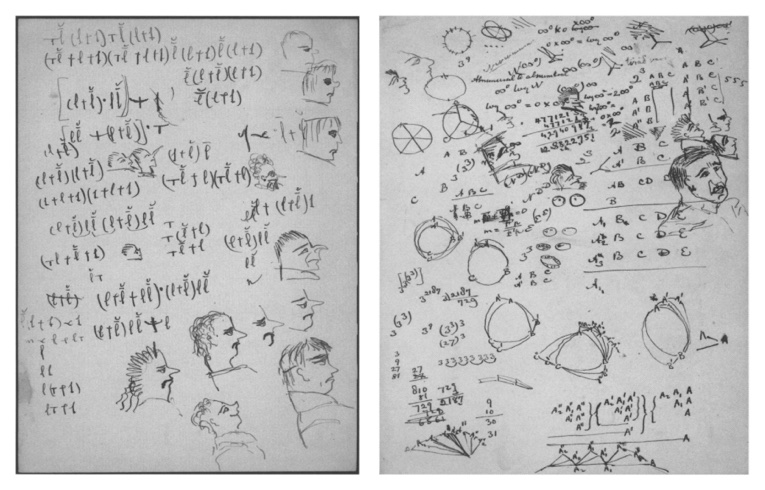

Pierce used visual diagrams from his youth to project his ideas.

«I don't think I ever reflect my ideas in words: I use visual diagrams, firstly, because this way of thinking is my natural language of self-communion, and secondly, because I am convinced that it is the best system for that purpose».

From an early age he was aware of this visual facet as a characteristic of his own mind, and developed his own method of representing his thoughts and arguments graphically, projecting their relationships to each other by means of diagrams. He called this language «ideoscopy», making explicit the link between ideas and visuality that he sought.

His worksheets were often illustrated with diagrams that serve to elaborate reasoning processes and mathematical concepts. His interest in puzzles of all kinds is evident in his papers; he playfully enjoyed them while analysing them logically.

The raw material of design is signs, in any of their meanings, which can be misinterpreted tomorrow in a very different context, or given a different meaning.

As I am sure that by this point in the text you are beginning to show signs of fatigue, and that our reality is dictated by very short attention spans, we will continue talking about American pragmatists later on. But not before leaving you with a small index of our next protagonist: ♥

Continue reading

This post is the first in a series of four on Pragmatism and Design:

- Charles Sanders Pierce (I)

Practical consequences, abduction and semiotics. - William James (II)

Mediation, body and emotions. - John Dewey (III)

Learning, experience and closure. - George Herbert Mead (IV)

Identity, social relations and objects.

Bibliography

Brag M. Pragmatism. In Our Time. BBC Radio 4.

Dalsgaard, P. (2014). “Pragmatism and design thinking”. International Journal of Design, 8(1), 143-155.

Kolko, J. (2010), «Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis«. In MIT's Design Issues: Volume 26, Number 1 Winter 2010.

Leja, M. «Peirce, Visuality, and Art.» Representations, no. 72 (2000): 97-122. Accessed July 9, 2020. doi:10.2307/2902910.

Peirce. C.S. “How to Make Our Ideas Clear”. Popular Science Monthly 12 (January 1878), 286-302.

Rylander A. «Pragmatism and Design Research». Ingår i Designfakultetens serie kunskapssammanställningar, utgiven i april 2012.