← Blog from Guindo Design, Strategic Digital Product Design

Design lessons from Athenian democracy

Some years ago we had the opportunity to visit Athens and the Agora museum. It was a very hot summer day. The Athenaeum of Attalus served as a little shelter from the hot sun. I found myself snooping around inside the museum, predisposed to see nothing but the remains of vessels and statues. When I began to discover, among the display cases, remains and traces of artefacts that looked more like the ruins of a computer made of stone, bronze and ceramics.

The Museum of the Agora of Athens, has a collection of inventions, designed for the daily and efficient management of one of the most complicated social entities of the ancient world. In Athenian democracy there are endless lessons in design at all levels, from the most strategic-political to the purely technological. At the risk of getting ourselves into a big garden, I think it might be interesting to refresh a little of its history. For hidden in its vestiges are design solutions that solve political and social problems, not very different from the ones we have today. Implemented by means of very simple ideas, and manufactured with extremely humble materials.

However, before extolling the virtues of our Greek ancestors, let us be clear about their basic flaws:

The “citizens” of Ancient Greece

As we all know, Athenian democracy was far from perfect.

To begin with, the role of women in Athens did not differ much from that of a Taliban caliphate, as they lacked political and legal rights. Condemned to be a minor throughout her life, under the authority of a guardian: first her father, then her husband, and finally her son or next of kin if she was widowed. The legal term for wife was known as damar, a word whose meaning derives from the root “to subdue” or “to tame”. The whole system was orchestrated around the citizens (all lords), who were an elite of males representative of their respective territories.

The social and economic system was sustained by slavery. For the Greeks it was seen not only as an indispensable reality, but also as a natural and necessary fact.

Foreign residents (Metecians) had no better rights either, and had to find a protector (or prostates) to settle in the city. They owned no house or land, at any rate they lived on lease from their protector and were obliged to pay special taxes. The law was not much on their side either. A citizen's sentence for murdering a Metecian was at most exile, while the death of a citizen at the hands of a Metecian led to death.

Certainly many of these situations have not improved much today in some parts of the world. Democracy, as always, has gone from strength to strength and is sometimes a mirage.

Origins of democracy

Between 670 and 500 BC, most of the Greek city-states had been ruled by one man. Dictators who seized power most of the time by means of a coup d'état. After the liberation of Athens from the tyrant Hippias in 510 BC, Clysthenes, who had been a magistrate during his rule, used his public office as a legislator to create the basis for a new state based on the equality of citizens (men, not slaves) before the law. Undermining ancestral rights by virtue of family inheritance or wealth.

Clistenes instituted a crucial and radical reform: the reorganisation of the citizenry into new administrative units or phylai (tribes). In his attempt to break the aristocratic power structure, he abolished the use of the old four Ionian tribes, based on family and power relations, and created in their place ten new ones.

In the new phylai, a new territorial redistribution took place. It was ensured that the territory of none of the new tribes coincided with the area of influence of an old aristocratic clan. In addition, all citizens were assigned equally to each of these groupings, mixing members of Attica families with ancestral rivalries. The regions of each tribe were further divided into districts (tritanies), areas comprising a city, a plain and a coastal area. In this way, members of the different tribes were prevented from having no personal contacts or common interests.

Here we have a radical solution to nationalism: divide up the territory as if it were a board game, mix the players among different teams, and distribute the resource cards equally. If only the world were that simple.

As mentioned above, each district or tritía had smaller units called demes (municipalities, villages or neighbourhoods), with their own local officials and administrators. In some cases, if traditional synergies between demes were close, the new system assigned them to separate tribes, in an attempt to break these alliances. This attempt to ensure equal representation also occurred in the Athenian administration. Each court jury had the same number of jurors representing each tribe. Public offices were also distributed as fairly as possible.

Building a new identity

But all this territorial design, more typical of the Catán board, had a problem that a priori seemed insurmountable: how could all these territories be socially cohesive? We are talking about mixing individuals who in the past had been fighting each other, and getting them to cooperate with each other. What is it that makes people feel a sense of belonging to a group?

To define the identity of the ten tribes, Cleisthenes had a brilliant idea. In order to satisfy the Greek custom of choosing a mythical founder for each territory, he sent to the oracle of Apollo at Delphi a list of the names of one hundred early Athenian heroes. The oracle chose ten (Erechtheus, Aegeus, Pandion, Leos, Achamantius, Aeneus, Cecrope, Hypoton, Ajax and Antiochus), the eponymous heroes, who served both to name the tribes and to create their emblems. Hence the term “eponymous”, which means naming a concept after a person.

In this way each tribe had its own “coat of arms”, an approach that is not far removed from how many people still build their identity and sense of belonging around mythomania: worshipping a football player, through an artist's fan club, or following an influencer.

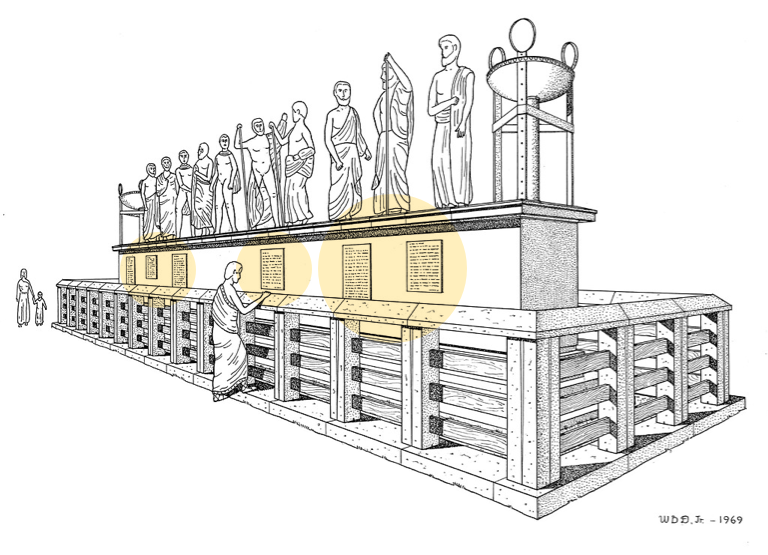

In the Agora in Athens, a platform was also built with statues of the ten heroes, where, in addition to worshipping the heroes, a public notice board was constructed at the base of the monument. Underneath the statue of each hero, announcements were hung that affected the members of their respective tribes.

The re-division of Attica was also probably carried out, or at least partly carried out, with a view to creating a new, more cross-cutting army model, as each of the tribes was to supply a regiment of soldiers. Shortly afterwards, in 501 BC, the Board of Generals (strategos) was introduced for the first time. Elected annually by the people, it had ten members who commanded the entire army. During the first period of democracy, it was the most important board of magistrates in the 5th century BC.

Many people on the move

Unlike previous forms of government, in which government had been in the hands of a single person, Athenian democracy depended for its legitimacy on a constant circulation of people in and out of public office. A constant flow of individuals, impersonal and representative, without a static structure of offices, which implied registration and identification for access to the organs of government.

The Athenian political system was essentially a daily tide of people on the move (officials, jurors, litigants...), going to symbolic places or precincts to cast their votes and opinions. After the liturgy of trials and assemblies, each citizen returned to his private life, where he lived according to the rules and verdicts he had helped to shape.

It was the beginning of the separation of powers and the specialisation of government into different bodies. A decision that was also intended to consolidate the “trustworthiness“ of the system, which was to be fraud-proof in any of its processes. The Athenians were very much chastened by corruption and tyranny. It is very curious how they relied for the most part on chance, as many of the exhibits in the museum show.

The allotment slips

One of the most striking objects in the Agora Museum are the so-called “allotment slips”. These are rectangular clay plates with an irregular edge cut like a jigsaw puzzle, designed to fit together. On these plaques, if you put the two pieces together, you can read the name of a tribe, a deme and some letters that have been interpreted as the abbreviation of a political office.

There are many hypotheses about the use of these tokens, but according to Mabel Lang, it is believed that the mechanics are as follows:

For each tribe, fifty complete tokens were prepared. On the back of each token the names of the demes were painted according to their representation in the council. Once the glaze was dry, the tokens were cut into two halves in the shape of a saw. The upper halves were then given to the representatives of the respective deme.

Once the representatives had left, the allocation of offices was done on the bottom piece, so that the corresponding deme could not be known. To do this, fifteen halves were chosen at random, where the abbreviated names of the positions were written, leaving the rest of the pieces blank. Then they were all mixed together until the day of the allocation of offices in the Hefestion, where the candidates of each deme presented their pieces and matched each other. The allocation ceremony was done publicly, turning over each piece, and announcing the result of the drawing of lots and the allocation of the fifteen apodektai (magistrates) per tribe.

The system was extremely simple, but effective in preventing corruption or influence in office. As children, we all played at passing secret messages to each other on cut-up paper. I certainly can't think of a simpler way to create an analogue certificate.

Too many people legislating

The citizens' assembly

All Athenian citizens were entitled to attend and vote in the Ekklesia, a popular assembly that met approximately every ten days in the grounds of the Pnyx. We are talking about a multitudinous meeting, as the maximum capacity of this space reached more than 13,000 people. You can imagine that these assemblies could become a real cacophony at times, nine members of the senate (the boulé) were in charge of establishing the order of turn, interrupting the discussion and establishing the order of voting.

Freedom of speech was essential to the idea of the assembly. Any citizen could speak regardless of their status, however, those over 50 years of age had priority. To bring some order, the herald was the person in charge of finding out in advance who wished to speak in the assembly.

The Senate

The boulé consisted of a group of 500 citizens, 50 representatives from each tribe chosen by lot each year. It deliberated and proposed laws to be ratified by all citizens in the Ekklesia. Such as the supervision of magistrates, ensuring a sufficient food supply and the defence of the territory, including the maintenance of the fleet. Elections and much of the financial administration were also under Boulé's control.

Too many people judging

People's courts consisted of at least 200 persons and could number up to 2,500. Court cases followed strict procedures. Before reaching a jury, the case had to be heard by a magistrate or arbitrators in a preliminary hearing. In some cases, the presentation of evidence or testimony was sealed for opening during the trial itself, using vessels similar to ceramic pots. The courts were also the supreme authority for interpreting laws.

The jurors

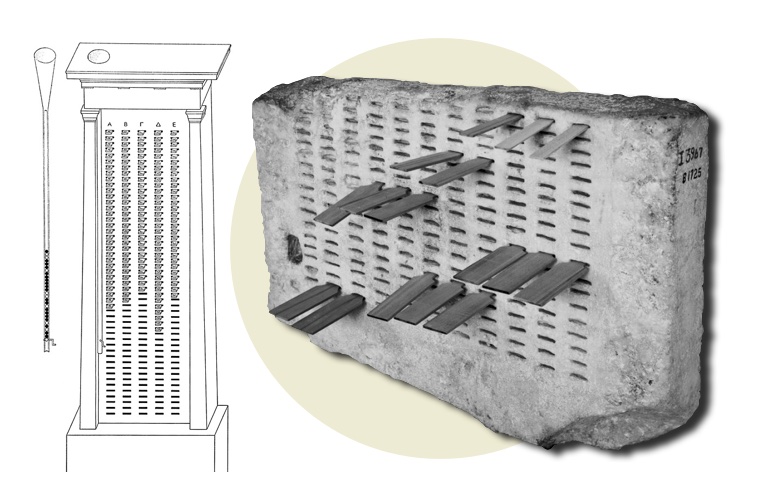

For each trial, jurors were chosen from a large number of citizens available to serve for a period of one year. At the beginning of the year, each juror received a bronze pinakion, which was one of the first identity documents ever created. It was a plaque on which was inscribed the citizen's name, his father's name and the deme where he resided (and thus tribal membership).

The pinakion were used in the kleroterion, devices that randomly assigned jurors to the courts. This device was a monolithic piece of stone, with horizontal grooves arranged in ten columns (one for each tribe). The allocation procedure was as follows:

On the day of the trial, the prospective juror appeared before the magistrate in charge of the adjudication. At the base of the kleroterion were ten baskets, one for each of the ten tribes. Before the beginning of each trial, the pinakion of the jury was deposited in its corresponding tribal basket. The magistrate would then take the pinakion from the first tribal basket and place them in each tribe's corresponding column of slots, until all the slots were filled.

On one side of the device was a hollow bronze tube, embedded in the stone, with a funnel at the top and a crank at the bottom. Through the funnel, the magistrate poured a handful of black and white balls, which after mixing would line up randomly in the tube. When the crank was turned, a ball was dropped, as in a bingo game. If it was white, the ten citizens (one member of each tribe) whose pinakions were placed in the first horizontal row would be assigned to that day's jury. If it was black, they were discarded. The procedure was repeated row by row until the court was complete.

This ensured a completely random selection, both by the order in which the pinakion were placed in the kleroterion and by the order in which the balls appeared. It also prevented corruption and bribery of the jury, as jurors were assigned just before the trial began, and ensured a diverse and equal representation with an equal number of members from each tribe.

The magic of this device is that the process of selecting judges became a spectacle, in which the gods activated the circuits of chance to designate their representatives. If we put ourselves in the head of one of the Athenian citizens, we might think that the kleroterion had a life of its own, or that it was a computer with access to the databases of Olympus. The kleroterion is such a fascinating machine that it has inspired several science fiction stories. Lately it has also become fashionable to link it to artificial intelligence projects, or dispute resolution through decentralised cryptography.

Once the trial was over, Athenian jurors were paid for their work on the spot. Another democratic procedure, designed to ensure that citizens could afford to serve justice, without affecting their household finances.

The speakers

Persons in litigation usually spoke on their own behalf, although occasionally they used professionals to prepare their speeches. Skilled rhetoric, charisma and theatricality were required to influence a jury.

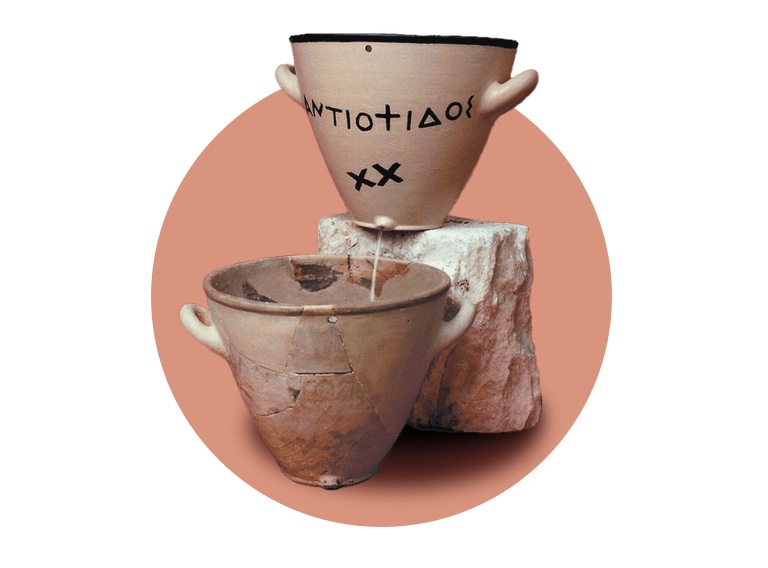

Trials lasted no longer than a day, there was a set timetable and speakers were allotted a limited amount of time. The maximum time for each speech was measured by klepsydra, water clocks consisting of two vessels, one placed on top of the other with a hole through which water was poured into the lower one. They were of different sizes, depending on the time required. The speaker could only speak for the set time, i.e. until the lower vessel was full. Experienced speakers, in order to create a greater climax, kept their attention on the stream of water and, as the pressure of the flow decreased, they concluded their speech, ending it just as the last drops fell.

The vote

Once the speeches and other evidence had been presented, the jurors took a vote in favour of either the prosecutor or the accused. Archaeological remains that have been found suggest that in the early 5th century BC the vote was not secret, as it was taken using pebbles and in public. But after the reforms of Clisthenes, the design of the voting system became more sophisticated.

The ballots were made of bronze pieces, similar to a spinning top with an axle in the middle. They were of two types, some with hollow ends (votes for the prosecutor) and others solid (votes for the accused). When it was time to vote, there were two jars in the courtyard, one made of wood and the other of bronze. The bronze one represented the valid vote, and had a fitting so that only one ballot paper could be inserted. When it was time to vote, one by one, the members of the jury placed their valid vote in the bronze jar, and the discarded vote in the wooden jar.

If the final verdict was guilty, then there was a second phase of the trial to fix the penalty. After several speeches, the jury decided between two possible punishments, one proposed by the prosecution and the other by the defence. Also, if during the vote there were not enough guilty votes (minimum one-fifth of the jury), the case was not considered worthy of trial and the prosecutor was fined. Yet another mechanism to avoid abuses of power and over-prosecution in everyday life, since experience tells us that most conflicts between people, if there is no serious harm involved, are usually resolved by talking and reaching an agreement.

The popular protection of democracy

The fall of Hippias also inspired the Athenians to devise further solutions to prevent the rise of new tyrants, or simply to penalise citizens who engaged in misconduct.

Once a year, the citizens met in the Agora and took a vote, to determine whether someone was becoming too powerful, and therefore in a position to re-establish tyranny. If a simple majority detected a potential tyrant, they would reconvene after two months. This second meeting took place at the foot of the hill near the potters' quarter, where defective shards of pottery were thrown away and recycled by the citizens for the vote. The name of the person they wished to exclude from Athens was written on these shards.

A minimum of 6,000 voters was required for this second final meeting. If a citizen's name appeared in an absolute majority of votes, he had to leave the city and was exiled for ten years, without losing his rights as a citizen. Perhaps because of the shape of these pieces of pottery, they were called “ostracon” (shell) and hence this condemnation was called ostracism. However, this procedure did not last for many years, as although it was an interesting idea, in practice it did not prevent a powerful citizen from using ostracism to eliminate a rival.

Conclusion

In short, and to avoid going into further garden-variety with issues that require a great deal more study, the Athenians designed a system that required a lot of coordination, mechanisms and technology to build trust. They had to do many things that today's information technology would have made much easier, and yet they managed to build, with the materials at their disposal, the tools they needed to make the system work.

If there is anything left of our civilisation in 2 or 3 millennia, archaeologists of the future are more likely to find the petrified detritus of our petrified dogs, inside their corresponding plastic bags, than traces of our best works and ideas. All of them encrypted and encoded in a language they may not understand, stored in a variety of devices and formats, reduced to dust in the occasional fire or climatic disaster. That's why I think it doesn't hurt to look back, from time to time, to humble ourselves and be inspired by the simplicity of the solutions of the past.

Bibliography

- Buitron-Oliver, D., Camp, J. “The Birth of Democracy”. American School of Classical Studies at Athens (1993).

- Dibbell,J. «Info Tech of Ancient Democracy».». Alamut.com (1998)

- Hansel M. «The Athenian democracy in the age of Demosthenes». University of Oklahoma Press (1999)

- Lang, M. “Allotment by Tokens.” History: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 8, no. 1 (1959): 80-89.

- Lang, M. “The Athenian Citizen. Democracy in the Athenian Agora”. American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2009)

- William, C. “Coastal demes of Attika”. University of Toronto Press (1969).