← Blog from Guindo Design, Strategic Digital Product Design

Biased views of User Experience

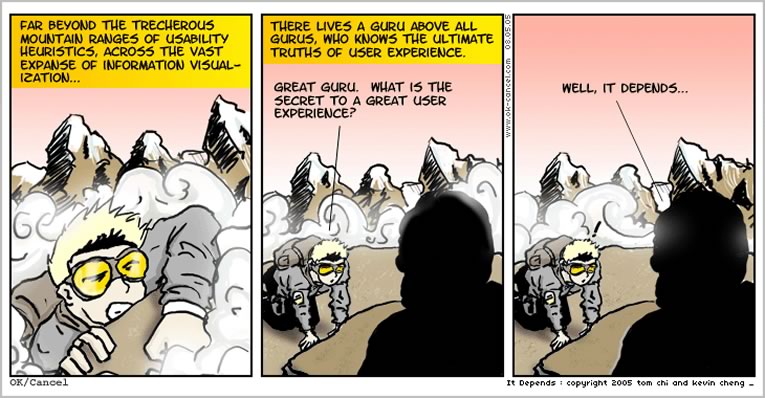

It is said that the job of the User Experience (or UX) professional is to explain what User Experience is. Although it may sound like a joke, nothing could be further from the truth. Behind a concept as vague as the definition of Art: the User Experience. creating and defining experiences through technology (in its broadest sense), it encompasses an amalgam of professionals with less in common than they would like as a collective and with sometimes completely opposing discourses.

The term UX was coined by Don Norman in the mid-1990s, when he was vice president of Apple's Advanced Technology Group, but it has its roots in ergonomics (or human factors). User experience encompasses all aspects of the user's interaction with the company, its services and/or its products.

But technology products and services are increasingly complex, and require a holistic approach to make them successful, as well as being evolutionary and flexible. It is a concept that encompasses so many disciplines, techniques and methodologies that to call oneself a “UX expert” is almost to proclaim oneself a deity.

Misunderstandings with the disciplines involved

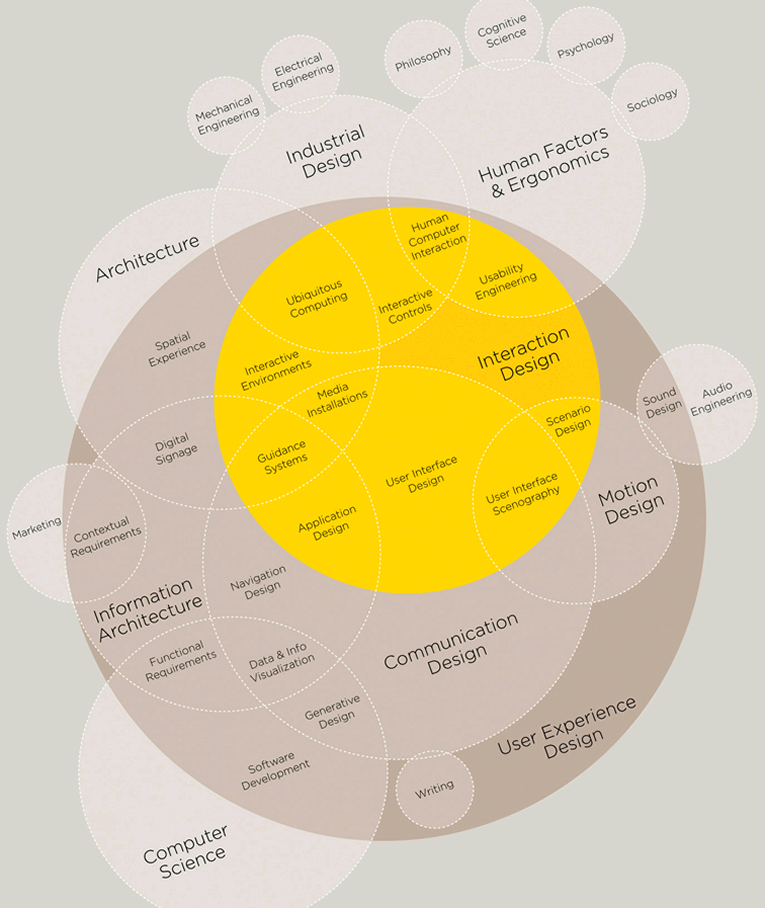

Dan Saffer designed for his book Designing for Interactions, a Venn diagram newly redesigned by Thomas Gläser, which attempts to take a panoramic picture of all the disciplines that interact in UX.

Despite this, there are many people who, even if they are professionally dedicated to one of these fields, continue to confuse the UX forest with a single tree. Let's take a look at some of the most confusing facets:

Interface design

It is very common to confuse “User Experience” with interface design, but designing screens is not the same as defining systems. Traditionally, the word “design” has always been confused with “make-up”, as the final varnish that embellishes the product, but design decisions are rooted in structure.

Aesthetics is an important aspect with a great impact on the final experience, but only if we understand design as a “process”, as a strategy, not as decoration, will we be able to contribute our grain of sand to the UX.

Moreover, since human-machine interaction can also be approached from other human senses (e.g. through gestural or auditory interfaces), the visual component should not be a decisive factor in the UX.

The latest technology

In many cases, R&D departments work on developing technologies and then look for a practical application for them; many technologies are imposed simply because they are new, with little time for users to become familiar with the old one.

The amortisation of a new technology can sometimes imply, for the user, the imposition of needs that did not exist before. Also, the desire to quickly adopt an emerging technology simply because it is fashionable (see the current mobile app bubble) takes precedence over the logic of finding the best technology to solve a problem in the simplest way for the user, or to provide the most value.

Usability

10 years ago, usability was a very fashionable concept on the internet, many of us who work in interaction design still use it as a spearhead in any project. However, there are many systems in which efficiency and effectiveness are not determining factors in UX: the learning curve, the visceral component and emotional responses are very important in some products and services (video games, entertainment, aspirational products...). However, it is true that any self-respecting UX professional must have internalised the basic principles of usability and ergonomics, so that they are always present, to a greater or lesser extent, balanced with other aspects.

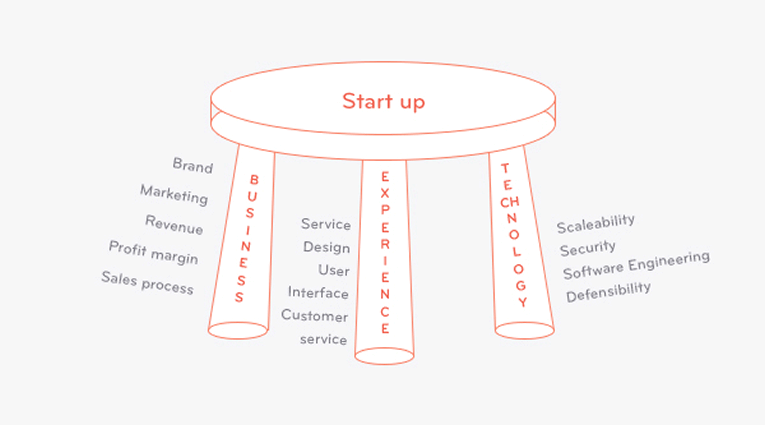

The user

The user is the focus of UX, but not everything has to revolve around the user. There are other aspects such as the viability and feasibility of the project that condition many decisions.

Although there are many projects whose objective of success is not economic, this does not mean that they should not be governed by the laws of viability and the market. How will the project be financed? How will users be acquired? What will the objectives be and how will success be measured? Technological constraints such as the platforms used, the scalability and security of the system must also be taken into account. It is not the same to carry out a project for a financial institution as it is for children, in both cases the security and confidentiality aspects are key, but they are governed by very different laws.

Another aspect that is often ignored is the people involved in the project, the team members themselves are also users, whose happiness and efficiency greatly condition the success of the project.

Disputes between methodologies, practices and processes

The sector has matured sufficiently for practitioners to specialise in many contexts and fields, which has also led to different and often conflicting methodological approaches. Let us look at some of the most recent controversies:

Activity-centred design vs. user-centred design

Activity-Centred Design is a high-level approach that focuses on tasks and goals rather than on the individual user, giving more importance to what people do, or what we as professionals want them to be able to do. It has its origins in the Activity Theory, one of the main psychological approaches in the former USSR, being widely used in psychology, education, vocational training, ergonomics and work psychology. The paradigm remained virtually unknown outside the Soviet Union until the mid-1980s, when it was picked up by Scandinavian researchers. This perspective can be very attractive in situations where the user base is very diverse and the objectives multiple, but the main activities are less numerous and easier to define.

One of the strengths of Activity Theory is that it bridges the gap between the individual subject and social reality, turning its attention to the psychology of work and learning.

Mike Long, in his controversial article Stop Designing for “Users”, promotes the idea that we should try to see the «big picture» of a system and how people interact with it, arguing that it may be better to look for common activities and design to strengthen them, rather than getting too close and focusing our design efforts on meeting the needs of individuals.

Advocates of this methodology warn about the dangers of “listening too much to users”: although the basic philosophy of User-Centred Design is to listen to them (taking their complaints and criticisms into account), acceding to their requests can lead to overly complex designs. It is also true that people adapt to technology and that the improvement of the tool itself facilitates our work.

Users will give us clues, but never design solutions. Design for all should not be designed by all, but by an authoritative professional who listens to users and translates their inputs into design requirements. Which brings us to the following controversy.

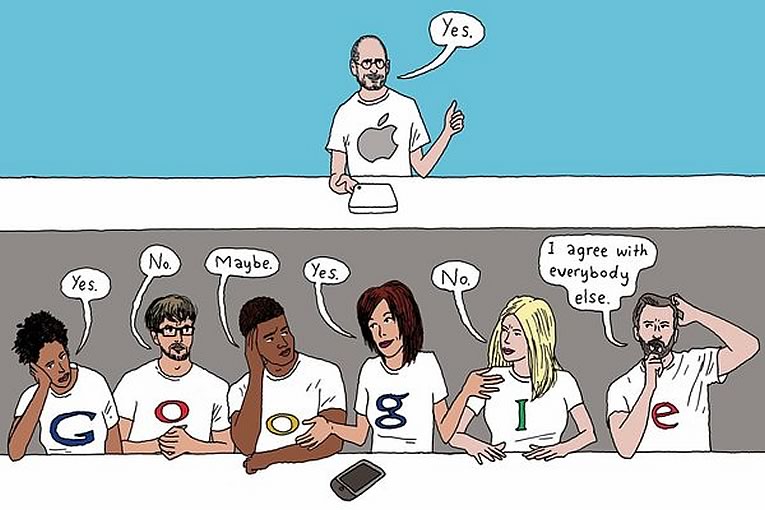

The lone genius vs. committee design

The traditional User-Centred Design methodology emphasises the importance of observing people using the interface, user research, testing and feedback from all stakeholders involved in the project. But this approach has many detractors who believe that this methodology has a tendency to create “design by committee”, which, while it may produce satisfactory results, is not geared towards creating outstanding or innovative solutions.

In contrast, the traditional approach to design still advocates the figure of the orchestra conductor. The creation of solutions directed by the expert designer who controls all the decisions of the project and with a clear, global and consistent vision.

Although a priori, the art director's approach may seem to offer the best solutions, it is in fact the exception that proves the rule. Geniuses are not plentiful and talent is a human capacity that is difficult to transmit in a very large organisation.

Then there is the risk of failure, for example Jeff Hawkins before creating the Palm Pilot, tried other PDA attempts (GRiDPadSize, Zoomer) that were not commercially viable. Many organisations, therefore, advocate the traditional User-Centred Design methodology, simply to increase the chances of success.

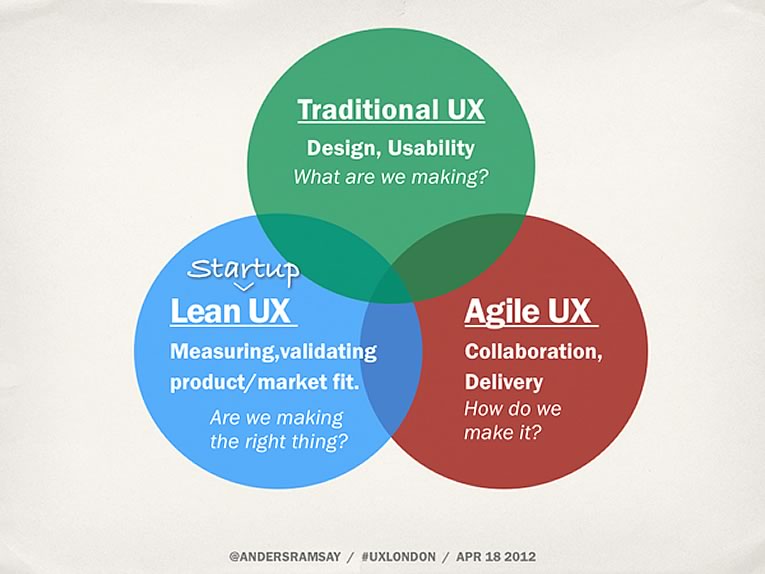

Lean UX vs. Agile UX

Lean y Agile are two very fashionable buzzwords in the industry, in reality it is simply a matter of giving more importance to two fundamental aspects of UX: the what and the how.

In the traditional UX model, research is something that is done before we start creating the product, to know what we are going to build. In a traditional lean, metrics are continuously created and collected on what we are creating. Experiments and hypotheses are continuously validated, prototyped and validated with users, in a continuous cycle of creation and testing.

Agile is a methodology created by developers who see product creation from their perspective, with the goal of creating high quality functional software in the fastest and most efficient way. But this implies the collaboration of people, and therefore the agile methodology offers a paradigm shift in the way teams work and especially affects UX professionals and their deliverables, which have to deliver documents oriented towards collaboration with developers.

The truth is that both methodologies can overlap according to the needs of the project, and each organisation tends to have the methodological cocktail that offers the best results.

Different organisations, different professionals

Possibly the two main factors that determine the difference between brilliant and mediocre design work are the context and the culture of the organisation: time, lack of resources, changes in strategy, conflicting priorities among members... As I said some time ago, the main factors that determine the difference between brilliant and mediocre design work are the context and the culture of the organisation: time, lack of resources, changes in strategy, conflicting priorities among members... As I commented some time ago Alan Cooper, The problems in the product are the signs that something is wrong in the organisation.

In general, the figure of the UX designer or expert in an organisation is closer to that of the manager. There are organisations in which they have a leading and directive role, and others in which they are more of a mediator between business and technology. Depending on the work context, the figure and role of the UX designer will vary to adapt to the peculiarities of the organisation.

Kim Goodwin, in his talk “Your Toughest Design Challenge”The User Interface 17 conference in Boston pointed out four types of organisations: adhocracies, clans, hierarchies and markets. According to Goodwin, each of them would require a UX professional profile with certain peculiarities:

Adhocracy

They are organisations in which there is general chaos, there is no consolidated process and things are always being reinvented. There is a certain resistance to documentation, but nevertheless they are organisations where novelty and experimentation prevail and are focused on growth.

UX professionals in an adhocracy are “whiteboard ninjas”, translating the group's vision into functional designs, rapid prototyping and gathering feedback from users and the rest of the team to move projects forward.

The Clan

Organisations where a lot of attention is paid to working relationships. In clans, things take a long time, everyone is involved in decisions. Meetings tend to be long and with many participants, there is no clear attribution of responsibilities and conflicts are avoided.

In the clans, the UX professionals are facilitators and coaches. Their work is very pedagogical and they invite the rest of the team to their research and design process, where the exchange of ideas and collective learning is enhanced.

The hierarchy

Highly specialised organisations. Hierarchies have rigid processes, roles and job titles, members are inward-focused and there is a certain risk aversion.

In fact, risk reduction is the biggest selling point in hierarchies, which is why UX professionals in a hierarchy are experts. They are trusted sources that ensure the minimum possible error in the implementation of projects.

The market

Marketplaces are outward-facing companies, where products are built on research, monitoring and agility. The role of the UX professional within a marketplace resembles that of a scientist, who can measure the implementation of all design decisions (however small) and demonstrate their impact through data analysis.

Regardless of the role within the organisation, the role of the User Experience Designer will be that of facilitator, educator, empathy builder and advocate for the user/customer. He/she is not only the expert on the user, but also the expert on the process. He/she has to know which tools and techniques to use depending on the situation and the state of the project, asking the right questions and making sense of the answers.

Top performers not only evangelise the principles and philosophy of user experience in their day-to-day work, but also engage the entire team and build a working culture throughout the organisation.

However, despite the enormous evolution and specialisation among professionals, there is still a sense of uncertainty and dynamism inherent in design work and the lack of absolute solutions.

UXSpain and the need for a meeting between professionals

Despite these differences and peculiarities, UX professionals have always been characterised by sharing resources and interests with the community in one way or another, usually virtually, and in recent years there had been a long period of time without any event that could serve as a pretext to devirtualise and bring together the UX community in Spain in the same physical space.

UXSpain was presented in its first edition last year, as a new opportunity to join forces, as well as a space for reflection and meeting to build community. The event exceeded all our expectations, with more than 400 people attending, and served as a trigger for other events and activities in different cities that have led to the launch of innovative proposals with which to continue learning.

For this year's edition, the meeting will continue to maintain its same philosophy, is organised on a non-profit basis and all proceeds will be used to cover the costs of the event. It will take place on the 10th and 11th of May in Valladolid and we will have a complete building at our disposal: the Palacio de Congresos Conde Ansúrez, of the Fundación General de la Universidad de Valladolid. We hope to enjoy it as much as we did last year.

Bibliography

- Bellomy, I (2009). UCD vs Genius: A Cursory Look

- Bry, N (2012). “From solitary genius to holistic approach” by Patrick Le Quément, world-class Design Manager

- Chi, T (2005). Activity Centered Design

- Cooper, A. (2011). The pipeline to your corporate soul

- Cummings, M (2007). What is UX?

- Hess, W (2013). The Enduring Misconceptions of User Experience Design

- Long, M (2012). Stop Designing for “Users”

- Merholz, P (2007). Peter in Conversation with Don Norman About UX & Innovation

- Norman, D (2005). Human-Centered Design Considered Harmful

- Ramsay, A. (2012) Agile UX vs Lean UX - How they're different and why it matters for UX designers

- Rowland, F (2013). Activity-centered design - some thoughts

- Saffer, D (2008). The Disciplines of User Experience

- Stross, R (2011). The Auteur vs. the Committee

- Traynor, D (2012). Asking Questions Beats Giving Advice

- Wilson M. (2013) The Intricate Anatomy Of UX Design

- Wroblewski, L (2012). UI17: Your Toughest Design Challenge