← Blog from Guindo Design, Strategic Digital Product Design

Proof of life

It's 7:00 in the morning, I've barely had time to put the dog on the leash for our daily morning walk, when I receive the obligatory WhatsApp message accompanied by the corresponding illustration or photomontage: “Good morning!.

Those of you who have school-age children, brothers and sisters-in-law or groups of ex-schoolmates will understand this very well. For more than a decade now, it's a rare day when I don't receive the little message.

At first I found them very annoying, when your day-to-day life is saturated with Slack notifications and emails, filtering the noise signal is exhausting. But over the years I've grown fond of them, I love the kitch aesthetic of these messages, and that someone takes the trouble to do it every morning has its merit. Good morning‘ is social glue.

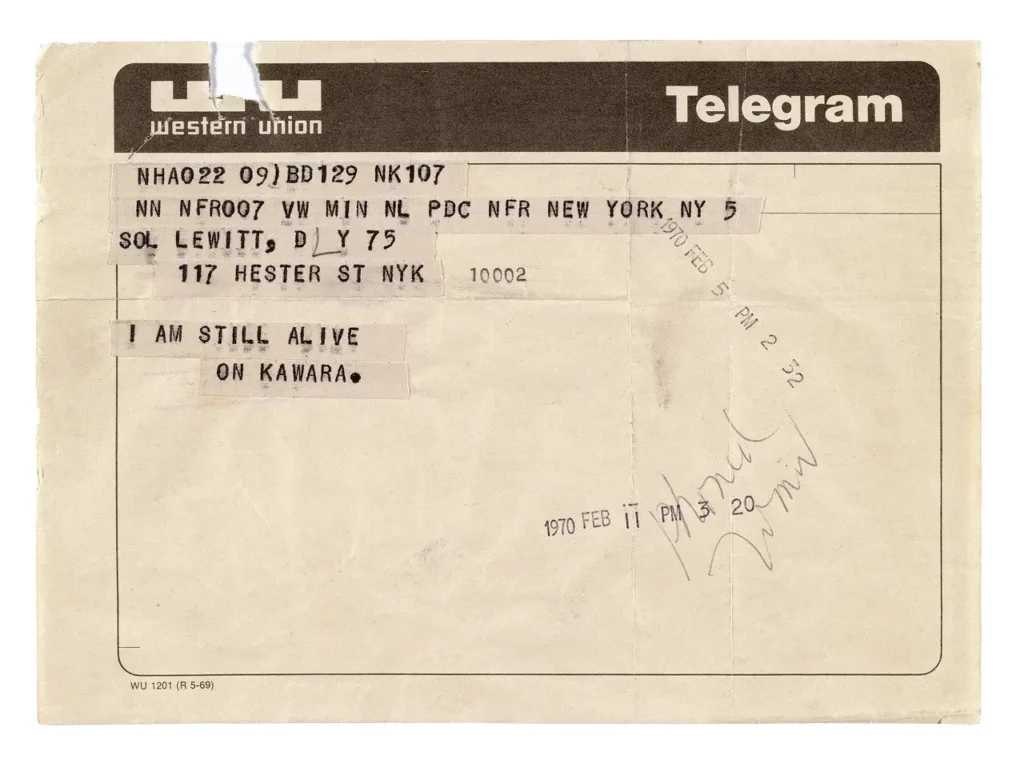

I am still alive

Now let's take a little trip back in time, imagine you are in 1970 and you receive a telegram. A telegram was something quite solemn and was usually reserved for communicating important news. Although some of this news was positive (births, weddings...), the telegram was often associated with bad news, including the announcement of a death.

You open it with trembling hands and read that a friend has sent you the following message: I'M STILL ALIVE.

On Kawara was a Japanese conceptual artist who decided to disappear in order to let time speak for him. Based in New York from 1965 until his death in 2014, he shrouded his figure in a mystique of absolute silence: he did not give interviews, did not allow himself to be photographed and his official biography consisted only of the exact count of the days he had been alive. However, this public absence was compensated for by an obsessive documentation of routine acts of his life. Through a series of postcards recording the time he woke up, his meetings, his travels, or simply totally aseptic hand-painted pictures, indicating the time he had woken up, his meetings, his journeys, or simply the time he had spent on his travels, he was able to record his life. the date of the day.

The series «I Am Still Alive»On Kawara's "On Kawara" consists of almost nine hundred telegrams sent to friends and colleagues, all with this same statement. What in the 1970s emerged from Kawara's own hand as a conceptual poetry act, a way of claiming sovereignty over its own existence has mutated today into a way of claiming sovereignty over its own existence. social need mediated by technology. For if Kawara used the telegram to assert his existence of his own free will, in today's China a tool has emerged that forces you to do so out of sheer survival.

Are you already dead?

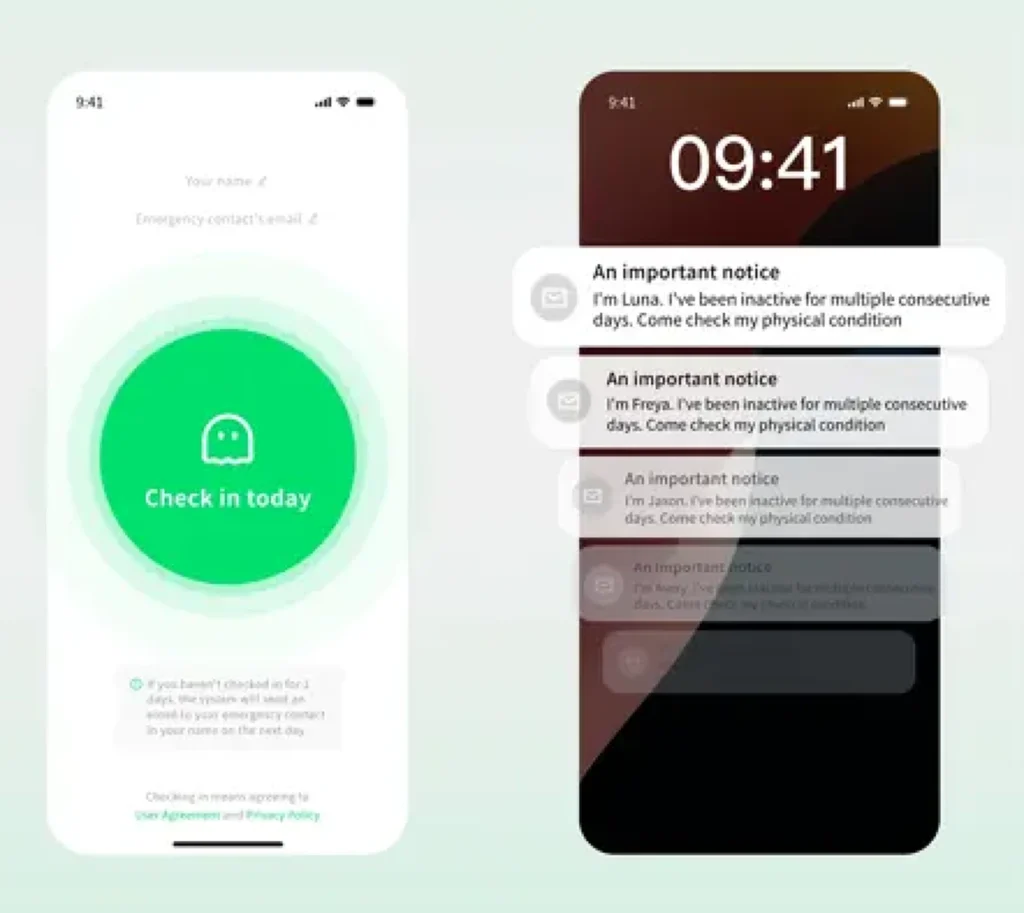

Just a few days ago, the virality in China of an independent application called Si-le-ma (死了吗), literally translatable to «Are you dead yet? Although it was launched in May last year without much fanfare, the attention around it has exploded in recent weeks, with it being downloaded en masse mainly by young people living alone in Chinese cities. The app was recently launched on an intentional level under the name of Demumu, a play on words combining the words “Death" and the name of the cuddly toy".“Labubu”.

The app has a single function, a large button that prompts users to press it once a day, so that if they fail to do so for two consecutive days, an email is automatically sent to a designated emergency contact, urging them to check on the user in person.

The developers of the project, all from the Z generation, commented in ainterview for Wired that were set in the Maslow's hierarchy of needs to create the project:

“We saw that the security needs are deeper and apply to a much broader group of people. It seemed like a good direction.

They went so deep into Maslow's Pyramid that they went to the crypt.

Si-le-ma has found its niche (sorry) in demographic isolation. In just ten years, the percentage of people living alone in China has risen from 14.5% to 25.4%. Against this backdrop, companies have shifted their focus from the elderly to an increasingly lonely youth, transforming the need for companionship into a lucrative new digital services sector.

«I'm worried that if something happens to me, I could die alone in the place I rent and no one would know. That's why I downloaded the app and set up my mother as my emergency contact».

This fear of administrative disappearance brings us back to the figure of On Kawara. Decades before our apps recorded our every move, Kawara was already operating as a human data collector. His work is a certification of their presence through routine. In its series I Got Up (1968-1979), he sent two postcards a day recording the exact time he left the dream to return to the world; in I Met, I created exhaustive lists of the names of every person I had interacted with that day.

It's the frequency, my friend

In today's digital environment, silence is not an aesthetic choice, but professional and social suicide. Platforms such as LinkedIn, Instagram or YouTube not only host content, but also impose a pace of production that researchers have begun to call «the frequency mandate».

Recommendation algorithms interpret regularity as a sign of quality and engagement. If a user interrupts their posting cadence, the system «punishes» them by reducing their organic reach. The result is a sense of constant vigilance, where the user feels that he or she must feed the machine in order not to disappear from the social map, thus generating a phenomenon that has been called the algorithmic anxiety, studied by researchers such as Kelley Cotter, who has published seminal studies on how users perceive and react to social media algorithms.

We no longer publish because we have something to say, but because the system requires a digital «proof of life». This pressure generates a phenomenon of redundant content. We publish for the sheer inertia of visibility, turning communication into an administrative formality to keep our profile active.

This obligation of continuous presence erodes mental health. In the same way that applications such as Si-le-ma We are prompted to confirm that we are physically alive, social networks force us to confirm that we are productively alive. We are trapped in a panopticon digital where the «policeman» is a frequency metric.

Good morning!

I don't know if my sister-in-law sends us these memes out of sheer inertia, out of that strange digital obligation to show signs of life, or simply because she remembers us. I'd like to think it's the latter, combined with a sort of black humour from the Groundhog Day. After all, On Kawara did the same thing for decades, sending a signal to his friends that, despite everything, the light was still on.

Tomorrow, when my mobile vibrates at 7:00 with that ‘good morning’ meme, I will no longer be angry or see it as digital noise, but a necessary smoke signal. That message will be my sister-in-law's private telegram telling me the most important thing that can be said today: that she is well, that she remembers us and that, fortunately, she is still alive.